-

ITFA represents the rights and interests of banks, financial institutions and service providers involved in trade risk and asset origination and distribution.Our Mission

ITFA represents the rights and interests of banks, financial institutions and service providers involved in trade risk and asset origination and distribution.Our Mission

Singapore, 5 April: The most severe stress case you can impose on any counterparty is their insolvency. So imagine your client has folded, there is no buyer for its business and all its staff has been dismissed. Apocalyptic?

Now imagine that your exposure to this client is paid off in full and on time. Exactly the sort of business you would want to do more of wouldn’t you think? But when that business becomes mired in the contagion of a story worthy of the celebrity press, it’s not surprising that questions are asked by even the most accommodating of credit committees.

So what just happened at Greensill? First, let’s try to understand the business that Greensill at least purported to engage in.

What is Supply Chain Finance (SCF)?

The term Supply Chain Finance (SCF) originated somewhere in the ‘Tower of Babel’ and has sown confusion ever since.

The Global Supply Chain Finance Forum (GSCFF), set up by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), International Trade and Forfaiting Association (ITFA), Factors Chain International (FCI), The Banker Association of Finance & Trade (BAFT), and the Euro Banking Association (EBA), has tried to undo the confusion by publishing the Standard Definitions for Techniques of Supply Chain Finance.

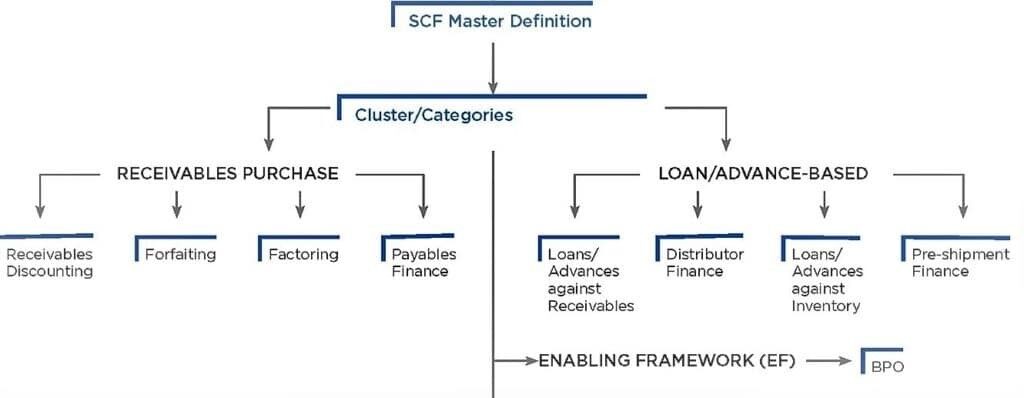

The document underlines the fact that SCF is a number of techniques with some overlaps, but commercially used at different points of the supply chain. These techniques include forfaiting, factoring, invoice purchasing, and, of course, payables finance.

Here’s what the environment looks like:

One of the key differentials is this split between receivables purchase and loan-based techniques. Bear that in mind as this story unfolds as it’s the key to one of the big revelations about how Greensill did business.

To the world, Greensill was engaged in what the GSCFF calls payables finance, but which many call reverse-factoring or simply, supply chain finance. The Standard Definitions contain synonyms for each technique and it’s not surprising to hear (remember the Tower of Babel image above) that payables finance has the most. In some ways, this doesn’t matter EXCEPT where these other forms of doing business are caught up in the same, negative publicity.

So, the first point is to understand here is that not all SCF is the same, which is where education comes. A good place to start is to go through the Standard Definitions and take up the ICC Academy’s Supply Chain Finance (SCF) course, which is part of the industry-validated Global Trade Certificate (GTC) and Certified Trade Finance Professional (CTFP) programmes.

Greensill did payables finance, but for the rest of the blog, let’s use the synonym most associated with it and call it Supply Chain Finance (SCF).

The need for Working Capital?

Like all SCF providers, Greensill tried to solve a basic problem that faces all businesses, especially the small ones.

Cash, more elegantly called liquidity, is king. A company with good cash flow, but low profits, will stay open for much longer than one with the opposite characteristics.

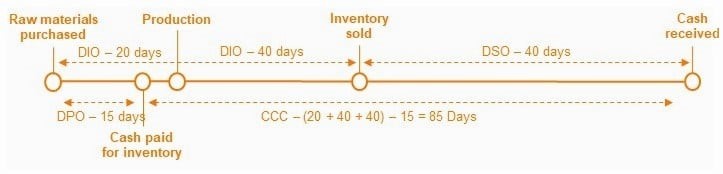

Working capital theory calls this the “Cash Conversion Cycle” or CCC. The CCC is defined as:

CCC = DSO + DIO – DPO

*DSO means Days

Sales Outstanding

*DIO means

Days Inventory Outstanding

*DPO means

Days Payable Outstanding.

A successful business will decrease its Days Sales Outstanding (DSO), that is, it will be paid as early as possible, reduce the days it has to keep unproductive inventory and increase its Days Payables Outstanding (DPO), which means it will pay its own suppliers as late as possible.

You can see this below in a worked example:

Anything over 0 means a funding gap. SCF is designed to tackle the DPO part of this equation. But any beneficial increase in the DPO from the point of view of a buyer will have an equal and opposite effect on its supplier who will see a corresponding increase in its DSOs, meaning, it is having to wait longer to be paid. SCF solves this problem by allowing both sides to win.

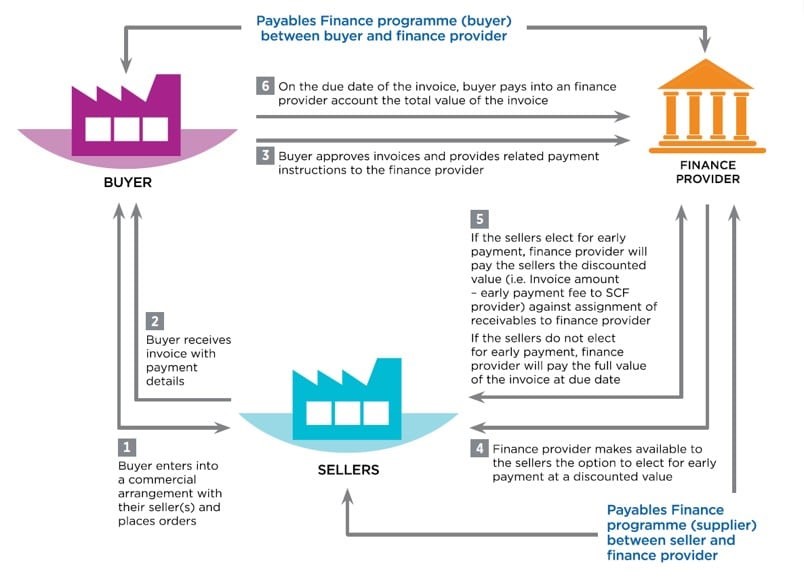

It does this by bringing both buyer and seller together and using a bank’s money to pay the supplier early at an agreed discount, which then waits to be repaid on the maturity date of the supplier’s invoice or receivable.

The buyer arranges the programme with the bank and will confirm to it that it is liable to pay the receivable to the bank unconditionally, often called an Independent Payment Undertaking very similar in effect to a promissory note. The bank usually also buys the receivable from the supplier, but it’s the payment undertaking that reassures the bank that performance risk is no longer an issue and it is dealing with pure buyer credit risk only pricing accordingly. The whole process normally comes together on a platform or through some other form of tech, making the experience as pain-free as possible.

Diagrammatically it looks like this:

Buyers arrange these programmes because it helps them to preserve the integrity of their supply chain which often consists of small suppliers who can only borrow or discount their receivables at much higher rates (remember the performance risk). Suppliers are not obliged to use the facility and can wait to be paid on maturity. They can therefore use it when they need cash faster e.g. to finance an acquisition or expansion at much more attractive rates than they would get from their own bank. Or to pay their workers on time when cash flows are out of sync with the payroll date.

SCF works best with larger buyers who are typically at or close to investment grade and have big supply chains. These programmes are very popular with the large supermarket chains for example. Big efforts have been made recently by a number of development banks to increase the range of buyers using this technique (ITFA has worked with the EBRD for example in Eastern Europe and the CIS to educate banks and corporates) by providing some sort of credit enhancement or protection.

Greensill’s own failed attempt to provide credit enhancement for sub-investment grade names was the immediate cause of its fall as we’ll see later. But note one important thing: there is nothing inherently wrong in trying to increase the use of SCF and have it deployed by smaller companies. Quite the opposite in fact, but the risks are far greater than with the investment-grade buyers and need to be understood by funders and investors. More about this a little later…

Of course, Greensill couldn’t fund all the programmes itself (the sub-investment grade exposure through the various funds it set up is estimated at US$ 10bn) and brought in banks and non-banks to finance these.

And this is where the Jekyll and Hyde split in its business model came about.

Greensill’s Business Model

The investment-grade names mentioned above were largely funded by big banks. This was, and is a rock-solid business and is precisely what I was praising in my opening paragraph. Greensill arranged this business, and whilst it used some of its own funds to finance a small part of it, largely stepped away once the transaction was arranged (focussing on generating new business from the same customers).

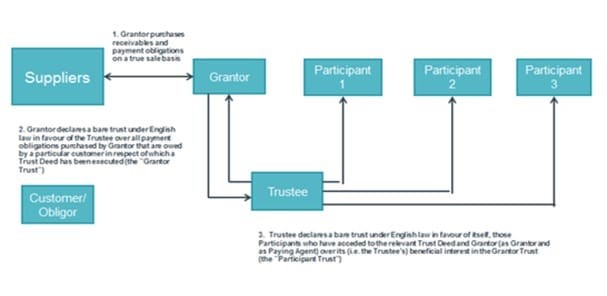

The structure put in place was designed to, and has, achieved bankruptcy remoteness from Greensill with funds passing through a trustee and paying agent. The structure used to achieve has been in place for at least a decade and whilst ponderous works and has survived this most acid of tests.

This is the double-trust structure that Lex Greensill, founder of Greensill Capital, knew very well from his earlier days as an employee of a very big bank. Another diagram to show how this works, (the grantor here is Greensill and the trustee is typically a big bank like Citi or Deutsche through their trustee divisions):

Some of the press has tried to characterise these trusts as designed to obscure cash-flows implying that their use was in some way sinister. Nothing, in fact, could be further from the truth.

The inconvenience of setting up and understanding these trusts has led to their gradual replacement by structures using the assignment as their principal legal prop but the aim is always the same: bankruptcy remoteness and a direction of cash-flows away from the arranger. Maybe poor old trusts are too tainted by their image as a tool of tax avoidance but that’s a lazy headline.

This kind of business is characterised by the prevalence of investment-grade buyers, the acknowledgment of the existence and validity of the payable by those buyers, and the consequent absence of the need for any additional form of credit enhancement. Yields on this kind of business are certainly better than cash and most loans, but they are not spectacular. At scale, that works for banks, but many investors want a more attractive return.

And here comes Mr. Hyde…

Greensill also established a number of funds that involved sub-investment grade names. Most banks won’t touch these, so these debts were packaged up to appeal to high-yield investors who liked the relatively short tenor of these debts and the credit enhancement that Greensill offered with these funds which were marketed by Credit Suisse and, for a while, GAM .

That credit enhancement came in the form of trade credit insurance. These policies essentially cover non-payment of specific and identified debts. Like all insurance policies, they are subject to contract terms and will only last for a period of time, usually a year. These insurers are investment-grade and adding their names to these funds will therefore make them more investable. Indeed, the constitution of the funds prohibited investment without some sort of suitable credit enhancement. Maintaining insurance was therefore critical to their continued survival.

Unfortunately, this didn’t happen. Whilst we will have to wait for the full details to come out, the cover was withdrawn by the single underwriter Greensill had put in place and couldn’t replace easily. The insurer declined to renew because of prior losses and some allegations that cover might have been placed in excess of the individual underwriter’s authority.

Greensill attempted to force a renewal of the coverage through court action but this was unsuccessful. As a result, the funds closed and Greensill very quickly started to unravel.

A few points should be made at this stage:

Firstly, credit insurers are entitled to manage their exposures like any other financial institution. They do this based on an appraisal of the risks they are presented with. Prior losses had caused them to be wary of the funds’ current composition and they showed excessive exposure to a single name or rather group of names in the shape of GFG Alliance, a family of steel-making companies.

This is not the place to argue the merits or otherwise of GFG Alliance, but the point is that the funds were now highly skewed to a single risk. And the single over-exposure to one credit risk also meant that the single weakest link of the funds – the ability to find insurance cover – was now tripped. Two weak links essentially played off each other and brought the whole game to an end.

But there is something else relevant to insurance which is even more surprising. As mentioned in the beginning, the split between receivables purchase and loan-based supply chain finance techniques. Payables finance – which we are calling supply chain finance – and receivables finance require the purchase or at least the existence of a receivable. Payables finance requires the buyer to confirm the validity and obligation to pay off his debt obligation.

The funds set up by Greensill for Credit Suisse mixed payables and receivables. Surprisingly, and the exact figure is not yet known, many of the receivables in the funds did not exist at all but were instead what is called “future receivables”. These are receivables which may come into existence in the future from projected sales or, possibly, even projected sales to projected customers. And the amount of time over which these receivables can be allowed to materialise can also be flexible, especially when financing is rolled over.

It was this kind of financing which seems to have alarmed BaFin which regulated Greensill Bank in Germany and financed some of this business. BaFin, it seems, were not satisfied that these assets had been properly accounted for and correctly described and therefore risk weighted. An even better insight comes in the form of the lawsuit filed in the US against Greensill by one of its former customers Bluestone Resources Inc. The complaint made an essential point that this is not payables or receivables financing and, in fact, given the very loose definition of a future receivable ( called “Prospective Receivables” in the lawsuit) it is highly likely, it is not even secured lending, one of the loan -based techniques referred to above. It is, in all likelihood, just unsecured lending and should be described and risk weighted as such.

The supreme irony is that Greensill’s insurer now seems to be arguing that it only covered “real” receivables and therefore may not pay out. Not all the facts are known and, given the amounts at stake, the issue will probably reach the courts (or be settled after a lawsuit). I think, however, that we would all have some sympathy for the insurer. It covered a specific risk and it turned out it was something else.

Trade credit insurance, as well as credit risk insurance, which is a slightly different market, has been called into question unjustly by the Greensill saga and that would be wrong. As the claims paid statistics show the pay-out figures are very good indeed. The insurance market strongly underpins the trade finance market and is a force multiplier for banks and, ultimately, their customers.

Another market or idea to suffer is that of using funds to repackage trade finance debt. It was the weakness of the Greensill/Credit Suisse funds that brought down the company and it is pure sophistry to argue that such funds are inherently flawed. The interaction of two weak links is what brought these funds down, but that is not a fact of universal application.

Transparency and understanding are key as they are in any investment. Bad timing or bad management also played a role here. A long list of “if only’s” will become apparent when you look over the Greensill story in detail. An enormous amount of work has been done by ICC amongst others to bring non-bank investors into this market. Remember the very low default rates revealed by the ICC Trade Register.

And a form of repackaging helped the “good” investment-grade business to operate efficiently and find funding banks. Many of these will have participated not by buying the debts directly but by buying notes from a Luxembourg multi-compartment SPV often used for securitizations and which is the beneficiary of the trust described above rather than the ultimate investors. This is the basis of ITFA’s TFDI initiative and a powerful idea it is too.

WHAT’S NEXT FOR SUPPLY CHAIN FINANCE?

Even prior to Greensill, SCF had come in for criticism.

Over a number of years, rating agencies have been expressing concerns over:

There are answers and counters to these concerns, but they are reasonable points to make and can be dealt with by informed debate and discussion. The guidance here that ITFA issued in 2018 continues to be applicable today and should be considered when assessing such programs. The red flags set out below continue to be critical:

It is also likely that the two accountancy standards boards, IASB (which regulates IFRS standards) and FASB (which regulates US GAAP standards) will intensify their review of supply chain finance. This had started last year and neither organisation had felt the need to make any immediate or urgent changes whilst keeping the issue on their agendas.

A few approaches are possible ranging from restating the financial position in its balance sheet i.e. recharacterizing the trade debt as bank debt, which is radical and, in the view of most practitioners, incorrect, to greater disclosure. The last outcome is the most likely and will have been accelerated by current events. The trade associations, as well as the GSCFF, support greater disclosure.

The Greensill story has shone the most powerful spotlight so far on supply chain finance. The industry has passed the test and the experience has allowed well-informed outsiders to truly understand the benefits of this powerful product which has served the business well during the pandemic.

About the author

This is a guest post from Sean Edwards, Chairman of the International Trade & Forfaiting Association (ITFA) and Head of Legal at SMBC Bank International plc, part of the Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group. He is one of the principal draftsmen of the Uniform Rules for Forfaiting (URF) (ICC Publication no. 800), a joint initiative of the ITFA and ICC and also a member of the drafting group for the Standard Definitions for Techniques of Supply Chain Finance. Sean sits on the Executive Committee of the ICC Banking Commission and leads a work-stream on the ICC Working Group on Digitalisation in Trade Finance.

Please note this is an opinion piece and Mr. Edwards’ views do not necessarily represent the views of ICC or the ICC Academy. For any clarification regarding Supply Chain Finance, we recommend you take the ICC Academy’s Supply Chain Finance (SCF) Course, which is part of our industry-validated Global Trade Certificate (GTC) and Certified Trade Finance Professional (CTFP) If you have any comments on this article, please feel free to reach out to Sean Edwards.

For more information, please contact

Priyanka Satapathy

Communications and Events Manager

Priyanka.Satapathy@iccacademy.com.sg

Privacy Policy | Cookie Policy

Designed and produced by dna.studio