-

ITFA represents the rights and interests of banks, financial institutions and service providers involved in trade risk and asset origination and distribution.Our Mission

ITFA represents the rights and interests of banks, financial institutions and service providers involved in trade risk and asset origination and distribution.Our Mission

By Dr. Rebecca Harding, CEO, Coriolis Technologies

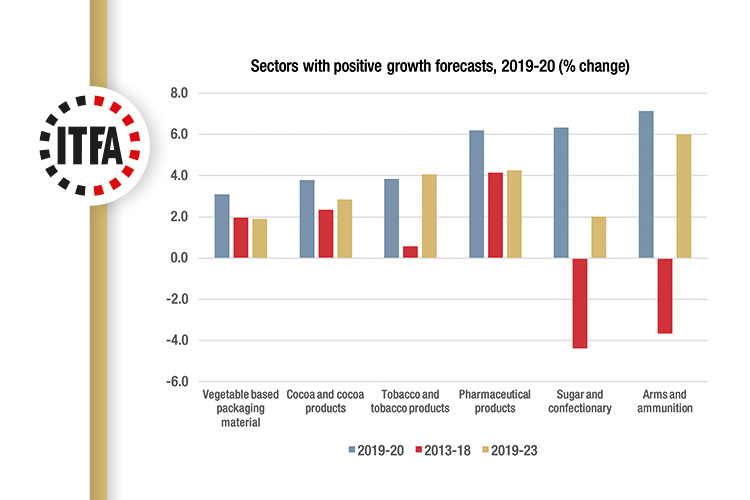

If you feel like you have over-indulged during lockdown, you probably have. Chocolate, sweets and confectionery, packaging, chemicals and pharmaceuticals and tobacco products are five of the six sectors globally whose trade in 2020 is set to grow according to the Coriolis Technologies forecasts (Figure 1). The sector set to grow fastest of all is arms and ammunition. As a world, we are online shopping, cleaning, eating and smoking our way through a year unlike any other in living memory while trade is literally weaponised. Sometimes data really does feel too real.

Perhaps reassuringly, every other sector in the world is likely to experience negative growth this year. We are expecting trade in commodities to be particularly severely hit, with oil, copper and iron and steel all likely to fall back in value terms during the course of the year by over 40%. This is unsurprising – the near-simultaneous drop in oil prices, equity markets and world trade that we saw in March this year mirrors the pattern of the Global Financial Crisis. We can expect the patterns in trade to be similar, not least because the correlation between oil prices and the value of trade is extremely high, and there is no sign that the price of oil will recover significantly.

This of course puts the oil producing economies back into their third price shock since 2007. Norway, Russia, Malta, Nigeria and Saudi Arabia are the worst affected and all are likely to see their value of trade decline by between 35% in Norway’s case to 44% in Saudi Arabia’s. But while Norway’s economy has the underlying strength, and wealth, to recover, Saudi Arabia’s oil dependency undermines its attempts at economic reform while the price of oil remains at below $70 a barrel. It has never recovered its economic growth after the oil price collapse in 2014 and 2015.

Unlike the financial crisis, this is a policy-induced economic collapse. At the beginning of 2020 there was a degree of optimism around: despite uncertainties around the rate of Chinese growth, the US election and Brexit’s impact on the EU and the UK, the year promised a reduction of trade tensions between China and the US, and as a result markets started the year off on a buoyant footing. But public health interests globally have taken precedence over the global economy and world trade has been its victim. Even if the WTO’s “worst case” forecast of a fall in trade of up to 32% does not materialise, it is very likely that the value of trade will fall by a similar amount to the financial crisis – by around 22% – because oil prices are still volatile and there are similar deflationary tendencies. The reaction from Central Banks makes the extraordinary monetary policy after the Global Financial Crisis look modest.

Trade is unlikely to be the same again. This is not just because we cannot be certain of the type of recovery we are likely to see. Discussion of a ‘V’ shaped bounce-back, a “U-shaped” steady return to growth or the depressing “L” shape where growth stays flat is a misdirection from the real issue: the world is going through a major structural change and this will impact everything.

Rather, it is because banks and businesses are investing in the rapid acceleration of digitisation which will change the way we trade as well as the way we finance trade. Businesses are likely to use the time now as a reason to accelerate automation of routine tasks, changing the way we work and not just where we work. Supply chains will shorten while the phrase “reducing dependency” has become part of a political as well as an economic discourse since the crisis: inventories have crashed because of their dependency on one supplier in automotives (remember the Jaguar-Landrover trip to China with suitcases to bring back components?), in electronics and most worryingly of all, in pharmaceuticals.

But perhaps most concerning of all is how Covid has pushed the world back to a nationalism that cannot be healthy for the future of trade. Over 95 countries in the world have imposed restrictive tariff regimes on products associated with Covid 19 medical supply chains, even within the EU. The United States has bought up supplies of the drug Remdesivir, walked away from the World Health Organisation and threatened sanctions on China because it thought it was insufficiently transparent about the origins and spread of the virus. China, in return, has imposed trade restrictions on Australia for agreeing that there needed to be an independent, global inquiry into its origins.

Covid has intensified the economic nationalism that has weaponised trade since 2016. China’s military expenditure has increased year-on-year since the Global Financial Crisis. Military expenditure in the EU and the US had been declining but has increased in the last two years. All this is evident in the trade statistics and this year is no exception.

It is unlikely that these weapons will ever be used – the conflict between China and the US is an existential one centred around financial and technological power. This is a new type of conflict, not a “war” in the sense of violence, but nevertheless aggressive and using “all means” to coerce and influence.

Trade is the tool in this war and we can expect it to be used more aggressively as the world tries to pull itself from its post-Covid torpor. The sanctions regime is likely to become more volatile and uncertain, and it will be increasingly difficult to escape the risk of secondary sanctions because of the technological inter-dependencies that are intrinsic both to what is traded and how it is traded.

What can the trade finance sector do about this?

Banks and businesses alike that believe in the power of multilateralism must fight to ensure that politicians know the damage that the collapse of the world trade system could do and show that it can adjust to the new structures that will be inevitable as a result of shifts in digitisation and supply chains that we will see. There will be opportunities – greater digitisation means that there is greater scope to support SMEs; localisation of supply chains is an essential first step towards greater sustainability. And if all else fails, keep eating the chocolate.

Privacy Policy | Cookie Policy

Designed and produced by dna.studio