-

ITFA represents the rights and interests of banks, financial institutions and service providers involved in trade risk and asset origination and distribution.Our Mission

ITFA represents the rights and interests of banks, financial institutions and service providers involved in trade risk and asset origination and distribution.Our Mission

By Izabela Czepirska, PhD and Pouya Jafari, ITFA Emerging Leaders Committee

Intro

As we entered 2021, the Brexit transition period came to an end and Great Britain and the European Union now face a new normal of customs duties and declarations when trading across the border. Much has been written since the referendum in June 2016 on the potentially detrimental effects of border controls and increased paperwork on trade, yet it remains premature to present a definitive assessment of the effects of Brexit on GB-EU trade.

Businesses are still adapting to the new rules and the intricacies of customs bureaucracy on the British side of the border will only be phased in over a six-month period. As for trade in services – which make up around 80% of UK economic output but were largely left out of the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) – we currently know little about where we will end up a few months from now.

With all this uncertainty, it is all the more challenging to assess the effect of Brexit on the trade finance industry. Nevertheless, some trends and lessons are beginning to emerge that ought to be front and centre for trade finance providers looking to navigate the present and plan for the future.

Trade in goods

Let’s start with an overview of trade in goods. Key themes and provisions in the TCA include tariff-free and quota-free trade in goods that primarily originate in the UK or EU, market access rights for haulage operators (but limited to a maximum of two journeys abroad before having to return) and airlines (with restrictions on the ability to service two points in the other’s territory), sanitary and phytosanitary standards, and technical barriers. An overview of these key themes and provisions can be found here.

Early reports indicate that many businesses are struggling to adapt to the new requirements, especially as they amalgamate with COVID-19 border protocols. According to a survey by the Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply, more than half of businesses importing or exporting goods through the UK border have experienced delays since 1st January. According to the survey, the main cause of delays is the extra time required for customs officials to handle the new paperwork.

Those statistics only take into account the businesses that are in fact trading, however. According to a Twitter post by the Road Haulage Association (RHA), exports from Britain to the EU fell by 68% in January. While the government has, according to Reuters, stated it does not recognise the figures, the decline in trading volumes is undoubtedly unlike anything witnessed in modern UK-EU relations. One British logistics expert described the situation as “akin to the country placing economic sanctions on itself” and added that “… now we’re just like walking through mud. There’s just paperwork everywhere”. On their end, many EU logistics providers are said to add significant fees to drive into Britain, in order to cover their costs in the event they return without goods.

Some industries that have been particularly affected illustrate how the new trading relationship creates frustration and disruption. In an open letter to the UK Prime Minister, Fashion Roundtable, a London-based think-tank, stated that “the UK’s fashion and textile industry, an industry which contributes £35bn to UK GDP and employs almost 1m people, (…) is at real risk of decimation by the Brexit trade deal and current Government policy”. The signatories to the letter highlighted that SMEs in particular cannot afford the additional burden of paying for red tape experts and additional tariffs.

Numerous associations representing the British music industry have also raised concerns about the new rules. In addition to the problem of musicians and crew requiring work visas for stays beyond 90 days in any 180-day period, permits are required for equipment and merchandise. Moreover, the two-trip limit on haulage mentioned above means UK performers will have to switch haulage operators once they arrive in the EU from the UK, adding major costs.

Furthermore, delays to trade in fresh produce have troubled the food sector, including the meat and fish industries. The new sanitary and phytosanitary checks can take hours, allowing food to rot. While these delays will likely be resolved in the coming months when processes align with the new requirements, the additional costs of £20 to £150 are large enough to eliminate the entire profit margin of smaller exporters.

Individual consumers also report facing additional friction and cost. Major logistics companies, including DHL and DPD, temporarily ceased cross-border deliveries toward the end of January and customers have complained of unexpected costs, including value added taxes and handling charges. For many consumers, cross-border purchases will no longer be economically viable.

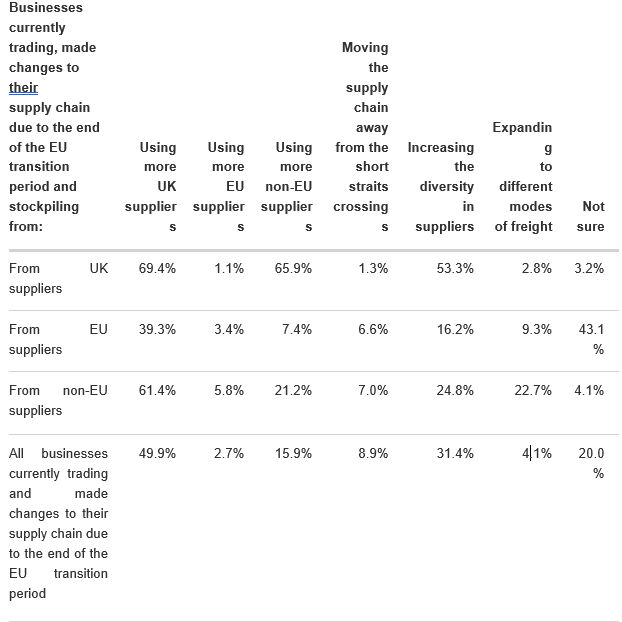

What is the implication of these short-term and longer-term changes to trade in goods for the trade finance industry? One implication is a shift in the make-up of supply chains and by extension a shift in supply chain financing needs. As of January 2021, 50% of businesses in the UK report using more UK suppliers due to the end of the EU transition period, according to a survey by the Office for National Statistics (ONS). This trend coincides with another persistent trend during the pandemic, which has been an increase in the number of suppliers that a buyer transacts with.

Many companies found in the last year that they were overly reliant on a few key buyers and that the time for frictionless just-in-time inventory management may be over, at least in part. A more diverse supplier base usually means relying on a greater number of smaller suppliers, allowing a company to quickly shift production between factories and countries in the event of supply chain disruption. This trend has increased the request for payables finance programmes; both to the size of credit limits and to include a greater number of suppliers.

Adding more (and smaller) suppliers, many of whom are struggling to remain profitable in the post-Brexit landscape is likely to drive more corporates to view payables finance programmes as a supply chain risk management tool, as well as a way to ensure their suppliers can trade on the buyer’s payment terms. It could also mean an uptick in requests for inventory finance programmes that allow companies to stockpile where they used to rely on a shorter inventory cycle.

Source: Office for National Statistics – Business Impact of Coronavirus (COVID-19) Survey

Trade in financial services

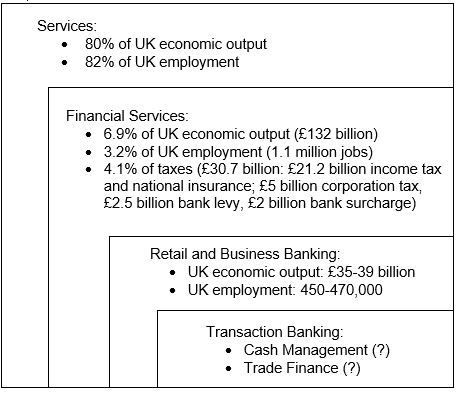

In order to assess the impact of Brexit on trade finance one would need to peel the layers of the onion from the services level, through financial services and business banking all the way to transaction banking. Afterwards, a split of transaction banking into cash management and trade finance would be ideal, but there is no data available at such granularity.

One month past the UK effectively leaving the EU, the impact assessment of economic output and employment even on financial services as a whole is practically impossible due to the unavailability of data. What could be observed, however, is how the estimations and scenario planning pre-Brexit have played out in the reality where the transition period expired on 31 December 2020, thereby removing UK access to the passporting regime and membership of the single market.

The UK Parliament report of 2016, European Union Committee Brexit: financial services, based on a study commissioned to inform the UK Government’s approach on the size of the financial sector and the potential impact of Brexit, outlined two extreme scenarios:

Whilst in the high access scenario with minimal disruption to the sector the losses were expected to be limited to £2bn of revenues, in the low access scenario wider impact on the ecosystem was estimated to magnify the losses to the level of £32-28bn revenues, leading to the reduction of 65-75,000 jobs, £8-10bn tax revenues and £18-22bn economic output.

In February 2021, one can consider the thin chapter on financial services in TCA as a symbol of the UK’s low access to the EU, where no detailed content on regulatory cooperation is included and removal of passporting rights becomes a fact. As it stands today, the equivalence agreement has been reached between the EU and Britain in 2 areas, while the original “Australian-style” deal enables Australian rules to be recognized in 17 areas of finance. This means it is currently easier to offer financial products to EU clients from Australia than from the UK.

Immediate consequences are noticed on the clearing of the euro-denominated stock market, where €6 billion in EU share trading shifted from London to EU marketplaces such as Amsterdam, Madrid, Frankfurt and Paris on 4th January 2021. As of 1st January 2021, the FCA has become the regulator of UK-registered and certified credit rating agencies (CRAs). Any UK legal entity that would like to issue credit ratings will now need to be certified or registered as a CRA with the FCA. At the beginning of January, the EU regulators emphasised that the EU and UK were distinct jurisdictions and withdrew registration of six UK-based credit rating agencies and four trade repositories for derivatives and securities financing trades. As such, EU investors will now be obliged to use EU-based entities data.

In line with prior expectations and arrangements in the payment schemes, as UK banks maintain access to the SEPA and TARGET2 infrastructure, UK consumers and businesses continue to be able to make credit transfers and direct debits denominated in euro. However, the charges levied on these payments have changed in multiple examples observed by UK banks as payment and clearing providers have included the UK in the non-EEA pricing chart. As London is now outside of the EEA, clients see an additional €15-20 charge on some payments. Due to the fact that there is no overarching framework, the approach applied by European banks intermediating in euro payments is not consistent. Interpretation and circumvention of the rules varies and as a result, some clients receive amounts lower than expected according to Iain Stredwick of Crown Agents Bank.

A majority of the large international banks have set up EU-based branches as their asset booking as well as client funds safeguarding locations. It is estimated that over $1.6tn of assets of large firms alone changed location from the UK to European financial hubs between the referendum in June 2016 and the end of the transition period in December 2020. What may cause further increases in the assets size booked away from Britain going forward, in addition to the smaller institutions’ move as of January 2021, is the fact that for legal and regulatory reasons, under the client money rule, European-based clients taking funds from their own EU customer base into their accounts outside of the EEA causes the funds to not be protected by the regulatory framework, regardless of the currency. Smaller banks put hope in the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) expected by March 2021 to cover this point on regulation and ‘transparency and appropriate dialogue’ on equivalence-related processes. The MoU on future cooperation on financial services is expected to provide clarity and agreement on common supervisory standards but it will not have the same legal force as an international treaty and will not immediately enable market access between the UK and the EU.

With jobs and companies shifting to continental Europe, it is not the EU’s priority to stop the outflow from the UK. While banks and large firms in the City and Canary Wharf set their hopes on the equivalence process – a weakened substitute for passporting as it can be withdrawn with 30 days’ notice and covers fewer market functions – the divergence from the EU has many supporters among hedge funds and the insurance industry. Hedge funds, unlike banks active in Europe, raise most of their capital from Asian and Middle Eastern investors. More flexible solutions could be adopted in the prudential and regulatory frameworks to suit them better than the EU Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive that was perceived as a big roadblock to their business model. Equally for the insurance providers, a review of the Solvency II regulation will be welcomed. These regime replacements could translate to an upside in business for trade finance active insurers as well as fund managers sourcing capital from non-EU investors.

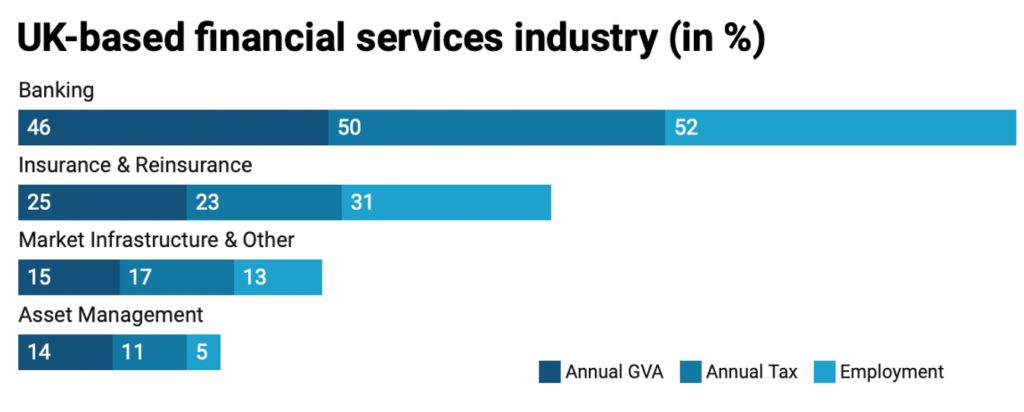

The charts below indicate the estimated contribution of the UK financial sector to Gross Value Added (GVA), measured as the economic output by ONS, annual tax as well as employment. The quantifications are split into 4 financial sectors: Banking, Insurance & Reinsurance, Market Infrastructure & Other, Asset Management by value and percentage. The last graph presents the largest segment of Banking: Retail and Business Banking, under which trade finance falls, which generates approx. £23bn a year in economic output (59% of total Banking), £11bn of tax revenue (56%) and employs around 385,000 people (82%).

*Annual GVA and Annual Tax in £bn; Employment in ‘000.

Source: UK Parliament analysis, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201617/ldselect/ldeucom/81/8102.htm

Source: UK Parliament analysis, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201617/ldselect/ldeucom/81/8102.htm

Source: UK Parliament analysis, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201617/ldselect/ldeucom/81/8102.htm

Conclusion

This article has attempted to provide some clarity to a messy picture. While the UK has officially left the EU, more agreements will be created, amended and implemented, and until those are in place it is difficult to offer any clear conclusions on the state of trade finance after Brexit. Moreover, distinguishing the effects of Brexit from the effects of the coronavirus pandemic is impossible at this stage. Yet, we believe a few lessons have already emerged: cross-border trade is permanently more burdensome and costly; supply chains are becoming more diversified and we expect that this will lead to an increase in payable finance requests; increased stockpiling could lead to an uptick in the use of inventory finance programmes; EU customer payment booking and clearing services will be conducted via EU bank branches; and alternative trade finance providers and insurance companies may benefit from new regulatory regimes. The trade finance industry is affected by each of these developments and will have to adapt to each change. Perhaps the only thing we can assert with complete confidence is that we shall stay busy for a long time.

Privacy Policy | Cookie Policy

Designed and produced by dna.studio