-

ITFA represents the rights and interests of banks, financial institutions and service providers involved in trade risk and asset origination and distribution.Our Mission

ITFA represents the rights and interests of banks, financial institutions and service providers involved in trade risk and asset origination and distribution.Our Mission

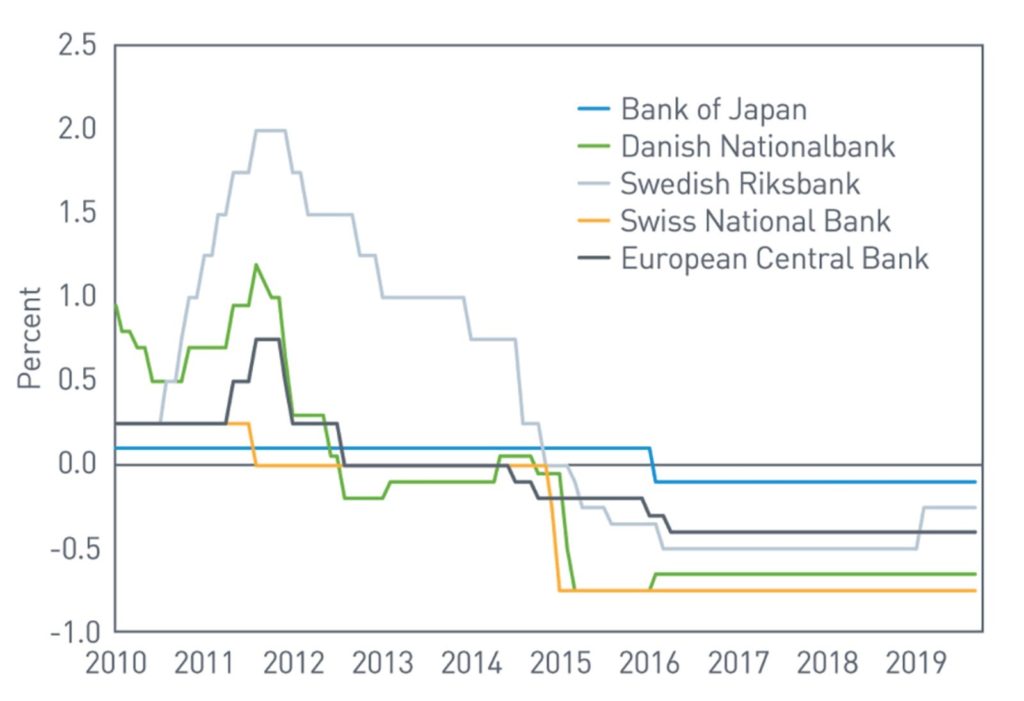

Negative interest rates are counter-intuitive. In a world where prudent savers are punished for saving and profligate borrowers are rewarded for borrowing, something is not on. The expression ‘time is money’ appears to have lost its logic. The trend began in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008, when the central banks of several developed economies embarked on unprecedented monetary policy (cutting policy rates to zero and purchasing huge amounts of government bonds) in an effort to stimulate inflation and economic growth. However, growth remained anemic and did not spur price inflation. As rates were already at zero, central banks began to pursue even more unconventional monetary policy, pushing rates into negative territory around 2015 (see chart below).

It must be said that nominal interest rates have fallen significantly in all industrialized nations since the 1980s. This is due to fundamental economic and demographic changes – which are not reversible. Growth and inflation rates have in particular fallen significantly. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), potential growth in industrialized nations has fallen from around 3% to 1.5% – despite technological advancement (which has not resulted in higher productivity), and average inflation from over 5% in the 1980s to 1.5% since the GFC.

Back to negative rates, these were expected to be a temporary measure to “shock” certain components of the economy, namely 1) stimulating credit and fueling demand for capital, 2) raising inflation and 3) depreciating currencies (and – in doing so – stimulating demand for exports, in turn helping GDP growth). The success of negative rates in achieving these objectives has been mixed so far – also due to the fact that, for example in Europe, not all economies are revving at the same pace. What is certain is that protracted negative rates have had a number of unintended consequences, some of which are creating significant social and economic challenges. Let us examine briefly a number of these.

Asset Price Inflation: Low and negative interest rates have resulted in significant distortions in global real estate markets, with prices in many geographies more than doubled from 10 years ago. The so-called investment plight attributable to the low returns on fixed-income investments is the main reason that has pushed real property prices up, making real estate virtually “the only game in town” for investors – increasing the probability of price bubbles forming in certain markets. As wages have not recovered at the same rate, this creates significant challenges for the younger generations to access the property ladder, accentuating inter-generational inequality to levels not seen before. A social corollary of this is that, in the future, wealth will most likely be transferred by inheritance than created by merit, affecting drastically social mobility. For the financial sector, these developments have resulted not only in narrowing interest margins but also in additional regulations governing provisions of mortgage loans, which were introduced by several central banks as a corrective measure.

Hoarding of physical cash: economic theory implies that negative rates should incentivize some depositors to hoard physical cash, in order not to be charged a cost for holding bank deposits – therefore stimulating productivity by “forcing” depositors to spend, driving consumption up, or invest their cash in riskier assets. However, most banks have so far been reluctant in passing negative rates onto depositors, especially retail, for fear of deposit flight. Today, retail deposit rates are still marginally positive in most economies affected by negative policy rates. Finally, there is a cost in storing your savings in actual banknotes, estimated at around 35 basis points for a deposit of EUR100k.

Mispricing of Risk: Negative interest rates also contribute to mispricing of risk, which adversely affects the allocation of capital and long-term growth prospects. In the current interest rate environment, investments and loans are being provided that could not be justified under normal interest rates. There is therefore a risk in a number of sectors that excessive, or unnecessary, production capacity will be built up. Overcapacity dampens inflation, perpetuating the rationale to keep negative interest rates in place. This phenomenon is known as “Japanification” and Europe is expected to enter into such pattern of economic conditions shortly. Also, negative interest rates significantly reduce companies’ interest costs. As a result, the threat of bankruptcy in the event of excessive leverage, which is central to a market economy, loses importance. The pressure to innovate and to compete decreases, which in turn has a negative impact on productivity growth and competitiveness. The rise in the number of so-called “zombie companies” that would have ceased to exist under normal circumstances can be observed in many countries.

Threatening Pension Funds Viability: There is evidence that the diminishing return outlook is forcing many pension plans to take on more risk, with underfunded plans particularly aggressive, according to a recent Federal Reserve paper. This may be dangerous not just to the funds themselves, but the broader financial system. In addition to negative rates, some pension funds are also becoming cash-flow negative, as assets continue to mature and are replaced by lower yielding assets. It has been calculated that, in the current interest rate environment, a worker starting his career today would need to put aside approximately 60% of his income, in order to accumulate a pension pot similar in size to those enjoyed by workers who have retired in recent years.

Fleecing the Banks: Negative interest rates lower bank interest margins and earnings potential. Because of this, banks are tempted to search for riskier loans and aggressively expand credit volumes, which can eventually increase the level of non-performing loans in a future downturn – and possibly cause a credit crunch. European economies are more dependent on bank credit than the US or the UK, therefore bank strategies are more closely correlated with the health of the economy. Banks need to redefine their strategies to counteract negative rates – which are here to stay-, at the same time facing competition from a number of new entrants in the financial services space (bigtechs and fintechs). Bank shareholders have certainly seen better times.

Privacy Policy | Cookie Policy

Designed and produced by dna.studio