-

ITFA represents the rights and interests of banks, financial institutions and service providers involved in trade risk and asset origination and distribution.Our Mission

ITFA represents the rights and interests of banks, financial institutions and service providers involved in trade risk and asset origination and distribution.Our Mission

By Clarissa Dann, Editorial Director of Marketing at Deutsche Bank Corporate Bank. This article was written from Sanjay Raja’s talk and presentation materials.

At the ITFA Annual Conference in Bristol Deutsche Bank’s Sanjay Raja shares his outlook for GDP growth, perspective on the tightening labour market, and concerns about inflation, after a strong start to 2021 that changed course as the year went on.

In his keynote talk, ‘How bright the dawn: charting 2021 and beyond’, given at the ITFA 47th Annual Trade and Forfaiting Conference in Bristol on 6 October, Deutsche Bank’s UK Economist Sanjay Raja set out a landscape that showed UK and other developed world economies with two dimensions.

Vaccine roll-out and economic bounce-back that had prompted headlines such as “Spring economic boom signals UK Covid recovery is still on track” (The Guardian 3 June), and “German economy on track for stronger growth in Q3 – ministry” (Reuters 19 August), made way for a darker perspective. “Britain’s trucker shortage jams post-pandemic recovery (Reuters, 3 September) and “Gas price crisis threatens to derail European recovery” (Financial Times, 20 September) were the voices of Q3.

Raja went on to share four themes that he admitted are keeping him awake at night as 2021 moves nearer its close. These are:

This article summarises his main insights in each of these broad areas of concern.

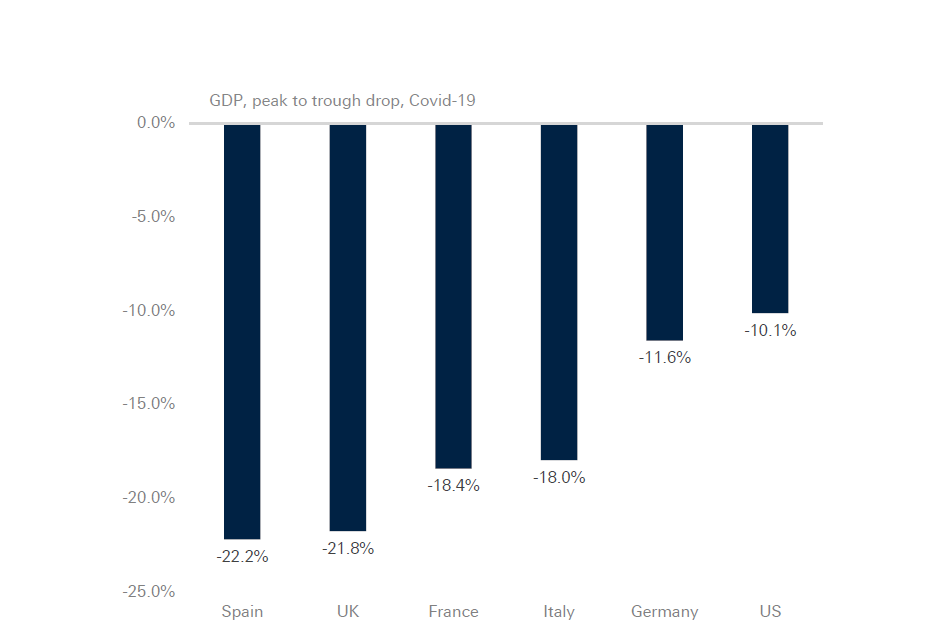

The unprecedented peak-to-trough GDP drops during 2020 were “historic”, the like of which “I hope we never see again,” said Raja. See Figure 1.

Source: Deutsche Bank, Macrobond

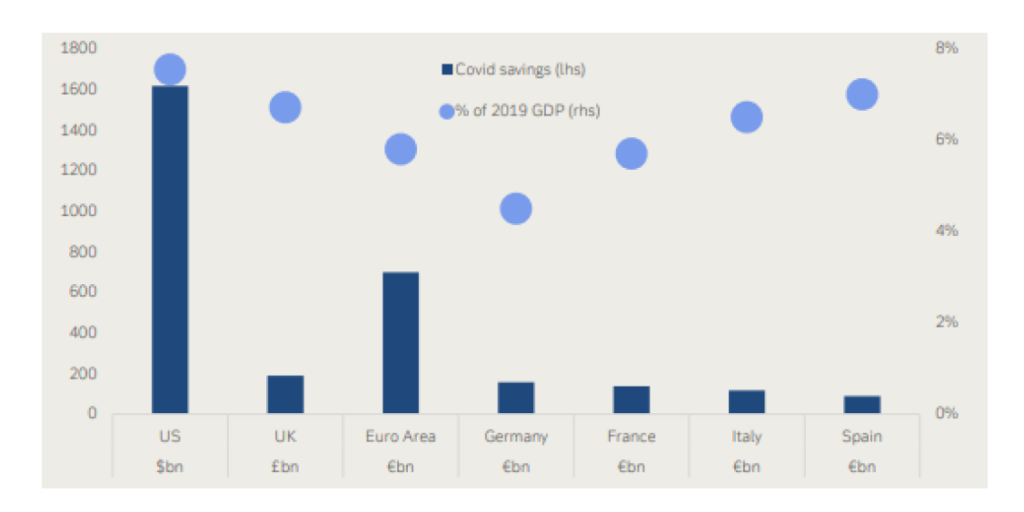

“What we saw across the world was economies building in resilience to restrictions that came in over last winter,” he continued. In the UK, for example, during lockdown in November 2020, GDP did not contract. And in Q1 2021 during the three-month lockdown, a further contraction of between 3% and 5% was anticipated by analysts – but output only dropped by 1.4%. Consumers and businesses had learned how to adapt to the restrictions which is why the steep GDP drop seen in Q2 2020 was indeed not repeated. The other contributor to the “huge jump in GDP” was involuntary/excess savings – in other words savings arising from restrictions that prevented individuals from spending their cash. As this built up – with the US hitting almost 8% of GDP during 2020 (see Figure 2), economists and central bankers were very optimistic, said Raja, about a significant recovery and assumed “unprecedented levels of demand and household expenditure flowing through various economies”.

Source: Deutsche Bank

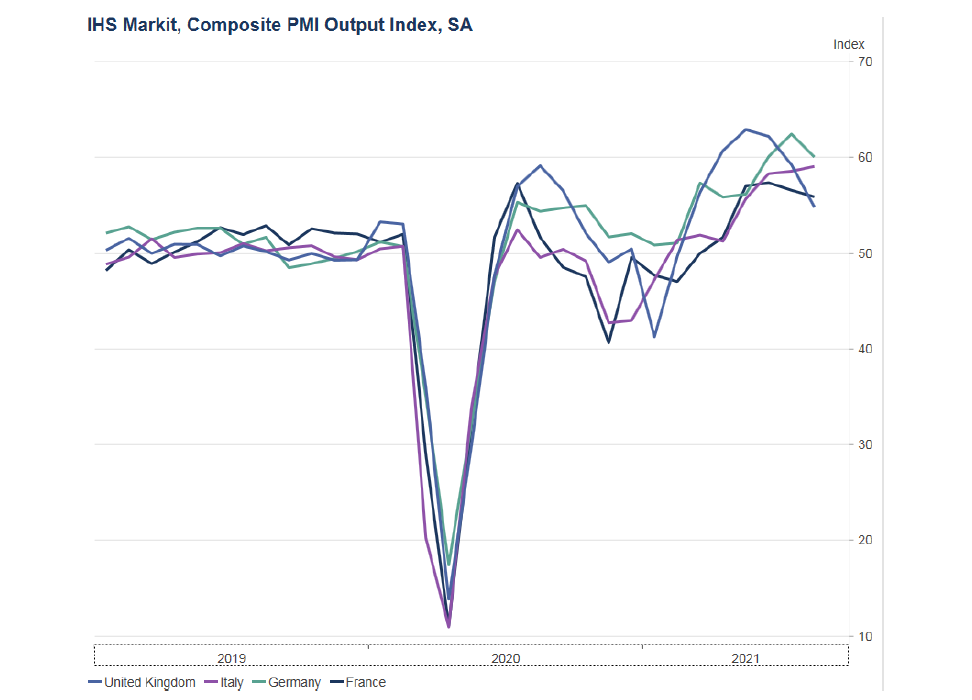

However, the anticipated growth bonanza did not happen, said Raja, but “while we knew that the jump in GDP was never going to last, the pace of that slowdown was not quite what we were expecting.” The US Purchasing Manager’s Index (PMI) is an economic indicator built from monthly reports and surveys from private sector manufacturing firms based on five main data sets: new orders from customers, speed of supplier deliveries, inventories, order backlogs and employment levels. As can be seen in Figure 3, the PMI Index demonstrates how output expectations were rising earlier this year but just after the summer they started to dip – and faster than anyone expected.

Source: Deutsche Bank, Macrobond

In the UK, restrictions were eased on 19 July (dubbed ‘Freedom Day’) and crowds flocked to Wembley Stadium for the Euro 2021 football matches. However, while the event should have contributed to stellar economic growth in July this did not materialise, and instead a slowdown was underway, recalled Raja. The excess savings were concentrated among high earners and the bottom decile had in the meantime got themselves into more debt.

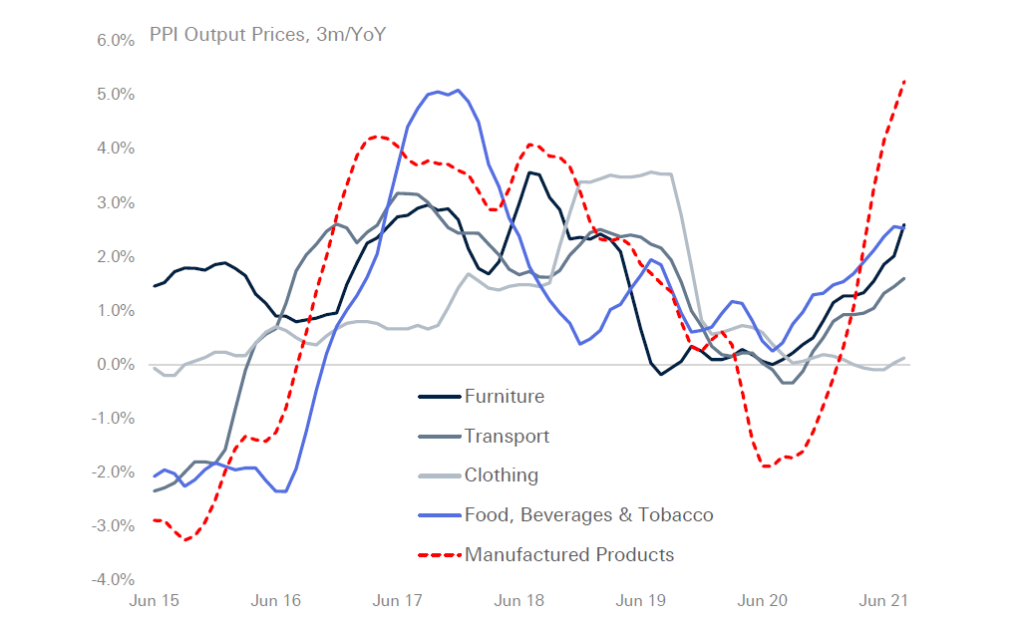

During the pandemic, both manufacturers and retailers deleveraged and ran down inventories as “nobody knew what the post- pandemic world would look like”. Going into 2021 and with the talk of growth surging, everyone restocked at the same time. Supply chain disruptions increased massively. “It was difficult to get goods across China and Asia to come into the developed world,” said Raja. He added that the TS Average Global Container Price Index shows how shipping prices have risen 50% since the end of 2020 and the US Freightos Freight Pricing Index tracked US West Coast Freight costs rising than 3.5 times since the start of the year. Supply constraints have put pressure on producer prices (see Figure 4) “you can see price pressures building through the economy,” he added.

Source: Deutsche Bank, Macrobond

Another problem that nobody saw coming, reflected Raja, was the contraction of labour supply. The various furlough and job retention schemes had ensured that the recession of 2020 was not accompanied by high unemployment, but the issue was one of labour market participation. He cited the large drops in non-farm payrolls, with the gains made earlier in the year eroded. Demand for specific workers is at an all-time high – it is not just transport but across the whole labour market. “Covid concerns remain front and centre for workers who have left the labour market,” he added, something that was expanded on further in the flow article, Point of no return (17 September 2021).

Source: Deutsche Bank US Economics, Haver Analytics LP

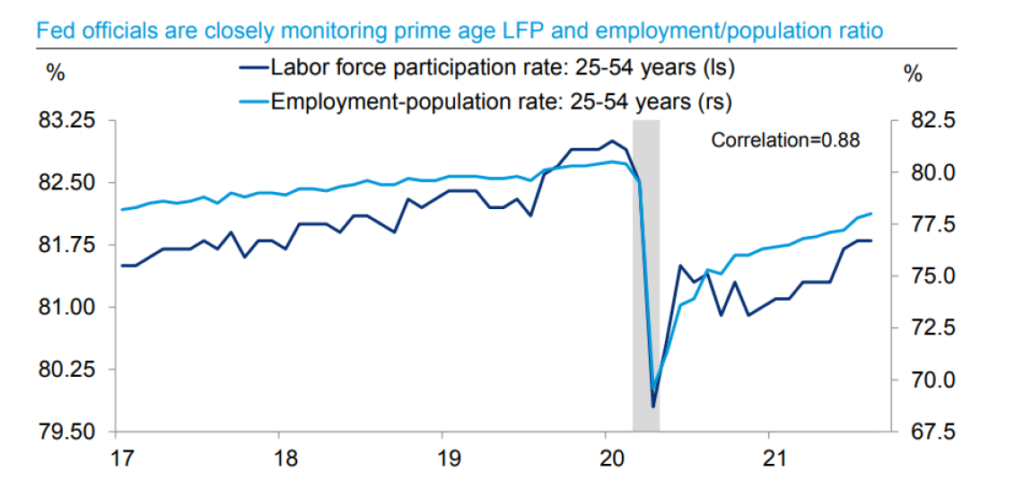

In the UK, the labour force has contracted by around 500,000. “One thing that shocked me was how slow people were coming back into the labour market, despite the introduction of vaccines and business sentiment improving materially,” Raja recalled. In the US, he explained, the Federal Reserve monitors the prime age labour force participation very closely along with the employment/population ratio (see Figure 5) and “you can see the gap we were at pre-pandemic to where we are at the moment in the US”. Unsurprisingly, the industries with the largest drops are those with high contact and the corresponding risk of contracting the virus – such as retail, leisure and hospitality and healthcare. In addition, female participation is pronounced in the US because of childcare problems and restrictions with schools and education. Over-55s who left the labour force during the pandemic returned in very small numbers (now representing less than 20% of the labour force against 41% before).

As a result of this contraction, businesses are struggling to find qualified applicants for their roles, which puts pressure on wages as the competition for talent intensifies. In the UK, added Raja, Brexit is also taking its toll with 200,000 EU nationals leaving the labour market at the height of the pandemic and only half of them since returning. “The UK not only has Covid to contend with but a second supply shock in the form of Brexit.” In other words, a smaller workforce usually means lower production levels. He pointed out that what we are seeing as we come out of the deepest recession since 1706–09 is that the lowest income earners are getting some of the largest pay rises.

Central banks have been monitoring inflation levels very closely. As former Bank of England Economist Andy Haldane put it in early 2021, “Inflation is the tiger whose tail central banks control. This tiger has been stirred by the extraordinary events.”[ii][DB1] In our flow article, US economy: timing is all Deutsche Bank’s US Chief Economist Matthew Luzzetti observes that how Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell “emphasised the importance to remain vigilant for evidence that inflation pressures are becoming more broad-based and thus persistent”.

The question that economists, traders and central banks are therefore trying to work out is for how long inflation will persist. At this point in the presentation Raja observed that the four hedges performing strongly are wholesale gas prices in the UK, gold bullion, and second-hand cars (the latter being exacerbated by the fourth item – semiconductors – that have been in short supply). Other triggers have been the pulling back of pandemic support and the tapering of quantitative easing.

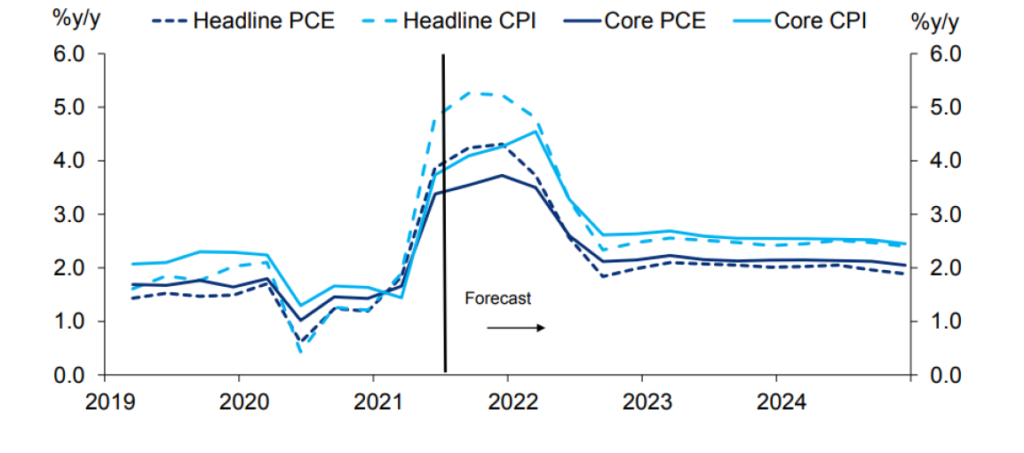

Deutsche Bank forecasts have US Consumer Price Index (CPI) peaking at little above 5% in 2022 (see Figure 6) before flattening out to 2%–3%.

Figure 6: Deutsche Bank US inflation forecasts

Source: Deutsche Bank

Central banks are cautious, said Raja, about the trade-off between economic growth and inflation, and the current light touch, based on the assumption we have transitory inflation, is far from reliable. The risks are again helpfully summarised by the Bank of England’s Haldane, “There is a tangible risk that inflation proves more difficult to tame, requiring monetary policymakers to act more assertively than is currently priced into financial markets. People are right to caution about the risks of central banks acting too conservatively by tightening policy prematurely. But, for me, the greater risk at present is of central bank complacency allowing the inflationary (big) cat out of the bag.”

Is it possible that a 1970s-style period of stagflation – when rapid inflation and high unemployment resulted from the oil price shock – could return? Raja thought this was unlikely, nor could he imagine the central banks would stand by and let this happen. On 18 October, after the ITFA event, he wrote in his UK Economic Notes paper, “the continued burst in inflation should leave the [Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee] MPC in a more uncomfortable position heading into the November meeting. Worries around household and business inflation expectations becoming dislodged are likely to rise over the next two quarters, adding some pressure on the MPC to lift the Bank Rate from its historic low more immediately.”[iii]

“The boom is over and

it’s all about supply constraints now,” Raja said in conclusion of his ITFA

presentation. In short, the labour market recovery “will be bumpy” and

inflation looks set to be more “sticky”.

[i] See also the flow article, ‘Inflation, where next?’

[ii] https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/speech/2021/february/inflation-a-tiger-by-the-tail-speech-by-andy-haldane.pdf

[iii] UK economic notes: Inflation Spotlight – September marks the calm before the spike (18 October) by Sanjay Raja

Privacy Policy | Cookie Policy

Designed and produced by dna.studio