-

ITFA represents the rights and interests of banks, financial institutions and service providers involved in trade risk and asset origination and distribution.Our Mission

ITFA represents the rights and interests of banks, financial institutions and service providers involved in trade risk and asset origination and distribution.Our Mission

Written by Robert Besseling, CEO, PANGEA-RISK, ITFA Member Institution.

To resolve Africa’s debt sustainability crisis, enhanced information and communication between the stakeholders will be crucial, especially to dispel false narratives and counter disinformation on Africa’s debt situation. As the ITFA’s newest member, specialist intelligence advisory Pangea-Risk seeks to inform the trade finance and forfaiting industry of key trends in Africa’s debt landscape and the potential for loan restructuring to act as a catalyst for new trade and investment on the continent.

At their annual Spring Meetings in April, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank resumed their Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable (GSDR) to help accelerate sovereign debt restructurings. Officially, the Roundtable seeks to “build greater common understanding among key stakeholders involved in debt restructurings, and work together on the current shortcomings in debt restructuring processes, both within and outside the Common Framework, and ways to address them.”

There is currently no formal structure to oversee or implement debt restructuring by sovereign nations, unlike international legal forums for corporate bankruptcies or individual defaults, and there has been mounting frustration over the slow pace of Common Framework applications in defaulted states, including African countries such as Ghana and Zambia.

Although there were several notable developments in the context of African debt restructuring announced at the latest Spring meetings, there is still no consensus between various stakeholders on how to replace or reform the Common Framework, which remains the only mechanism led by the Bretton Woods institutions and the Group of 20 (G-20) that brings together both Paris Club and London Club creditors, as well as bondholders and China, now the world’s largest bilateral creditor.

In March, Pangea-Risk published a white paper, along with Acre Impact Capital, that provides an alternative view on African debt sustainability risks and assesses the outlook for debt restructuring in key African markets going forward (see https://www.pangea-risk.com/white-paper-the-politics-of-african-debt-restructuring/).

The role of multilaterals in debt restructuring

The GSDR was launched in February this year and resumed for a second meeting at the IMF-World Bank Spring meetings in April. The roundtable is co-chaired by the IMF, World Bank, and the G-20 Presidency (currently India) and comprises official bilateral creditors (both traditional creditors, members of the Paris Club, and new creditors), private creditors, and borrowing countries. Importantly, the GSDR does not replace existing restructuring mechanisms, such as the Common Framework. Instead, it seeks to support those mechanisms by fostering greater common understanding on concepts and principles, which it is hoped will in turn facilitate individual restructurings.

The latest GSDR meeting comes amid continued delays in securing debt treatment agreements for Common Framework applicants Zambia, Ghana, and Ethiopia, which officials from the United States and others blame on stalling by China. Such allegations are based on claims that Chinese financial institutions, such as the Ministry of Finance, central bank, and state lending agencies, are not collaborating, while also remaining reluctant to agree to any loss on their loans, i.e., a haircut. At the April meeting, the roundtable agreed on the importance to urgently improve information sharing including on macroeconomic projections and debt sustainability assessments at an early stage of the process.

The meeting also discussed the role of Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) in debt restructurings through the provision of so-called “net positive flows of concessional finance”. In other words, the stakeholders agreed that the International Development Association’s (IDA), which is the World Bank’s main lending arm, will significantly increase lending to distressed countries. The World Bank has approximately USD 70 billion in lending capacity for Africa, which African leaders are calling to be tripled. Other African countries are also calling for another issue of the IMF’s special drawing rights that would be allocated for African countries. SDRs are a form of reserve asset of which USD 650 billion’s worth were distributed to the fund’s member countries at the height of the pandemic in August 2021. However, at the time only a very small fraction of the SDR release went to African countries, and wealthier countries failed to agree to redirect their own SDRs to poorer countries.

A key accomplishment of the April meetings is that China agreed to back off its insistence that multilateral lenders such as the World Bank, which provides low-interest loans and grants to poor countries, accept losses in the debt restructuring. The World Bank dismisses that demand, arguing that development bank financing already comes with low interest rates and does not add significantly to a country’s debt burden. Multilateral lenders have long been ranked as “super-creditors” which are exempt from taking losses on loans. In exchange for China’s concession, the multilaterals seem to have agreed to step up lending to emerging markets.

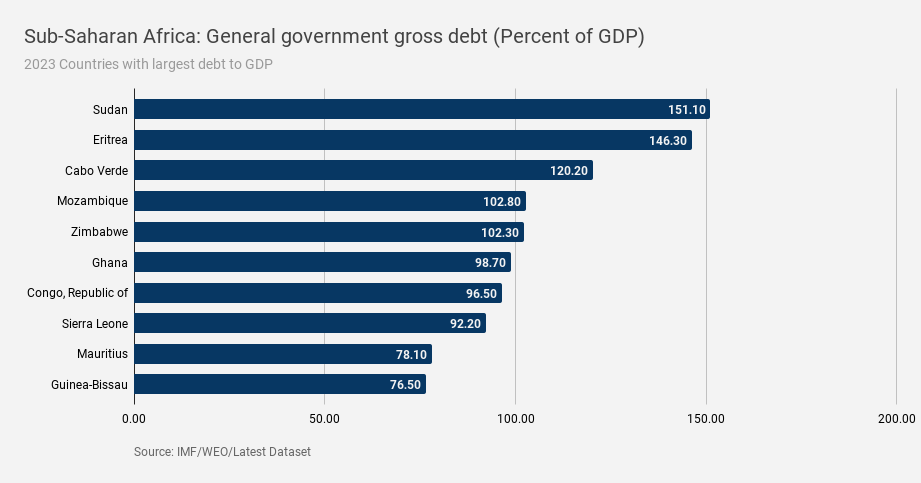

Africa’s mounting debt burden

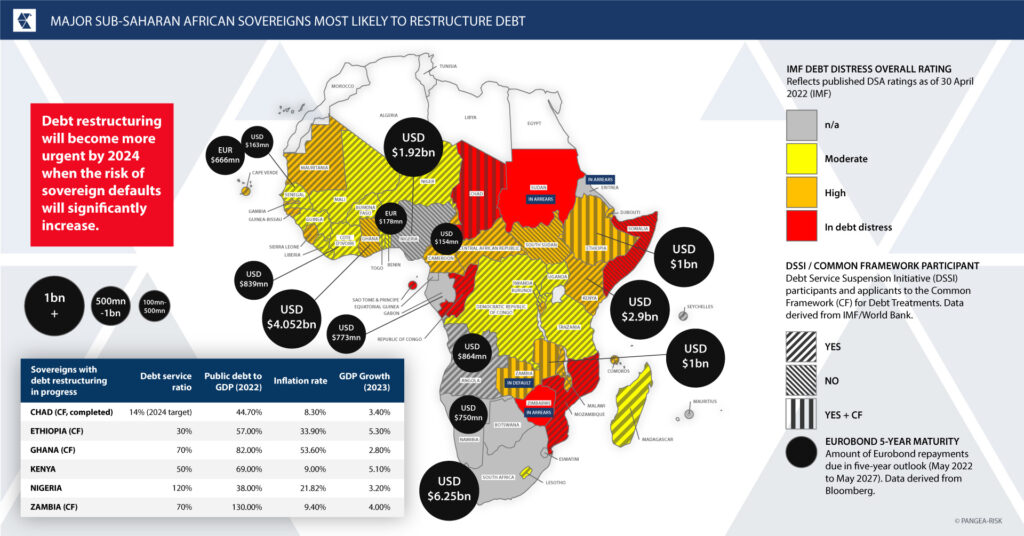

Africa’s private and public external debt, which increased more than fivefold to more than USD 700 billion from 2000 to 2020, is no longer sustainable. Based on the latest rankings by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), 22 low-income African countries are either already in debt distress or at high risk of debt distress. In late 2020, Zambia began to default on its Eurobond coupon payments, raising concerns that a “domino-effect” would sweep through other distressed sovereigns, especially from 2024 onwards when large capital repayments are due on many international bonds. However, such fears have so far proven unfounded, as many so-rated distressed sovereigns are voluntarily restructuring their debt in innovative, transparent, and credible ways.

Since the onset of the pandemic three years ago, African sovereigns have mostly avoided messy default scenarios like Zambia’s and instead have actively engaged with creditors to restructure their obligations in coordinated and voluntary schemes. Kenya, Ghana, and Nigeria are currently exchanging most of their costly domestic debt for more affordable obligations, such as long-term bonds, concessional finance, and other instruments. On the external front, there has been less progress, which is mostly due to the infeasibility of the Common Framework, which replaced the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) in early 2021. Only four African countries have applied to the framework – namely, Zambia, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Chad. Only the latter has been able to forge an agreement, although Chad’s debt reprofiling was mostly a bilateral deal with commercial partners, rather than a multilateral debt treatment.

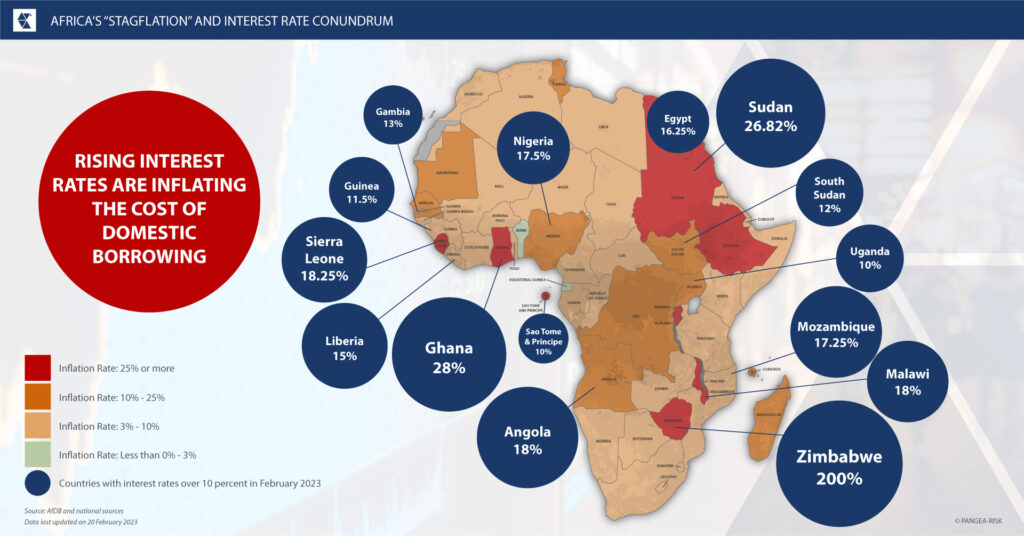

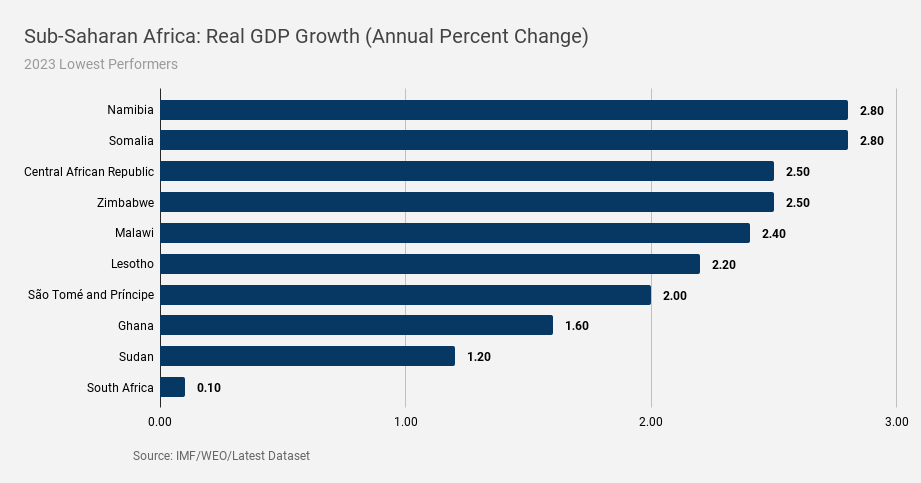

The IMF expects annual growth in sub-Saharan Africa to slow from 4.2 percent to 3.6 percent this year, as its countries suffer a big funding squeeze tied to the drying up of aid and being frozen out of global capital markets. The sharp increase in global interest rates had raised borrowing costs for sub-Saharan African countries, on domestic and international markets. Not a single country in the region has been able to raise financing through a dollar bond sale over the past year.

A Chinese debt trap?

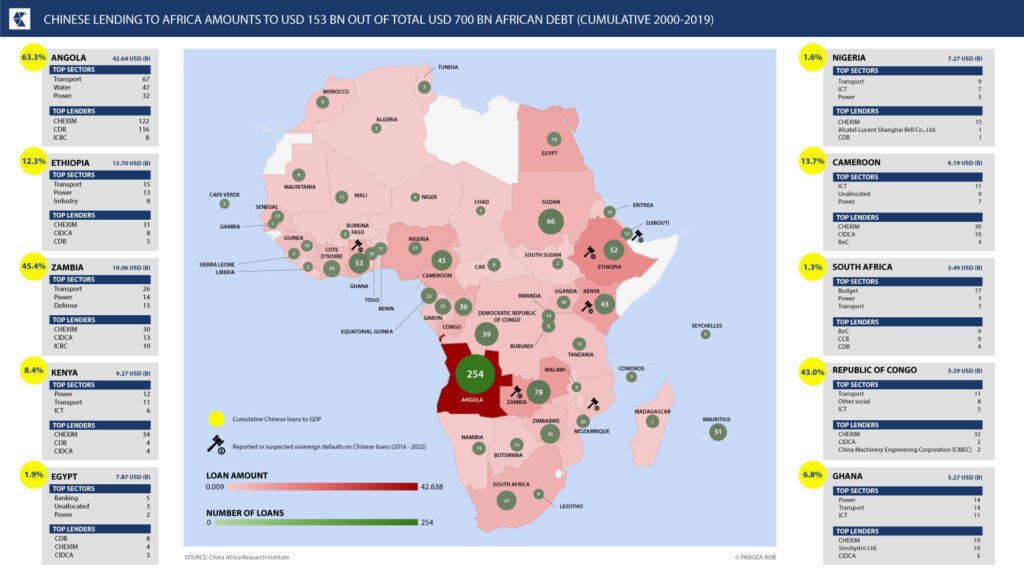

Even while the Common Framework has been slow to forge agreements on external debt, several African sovereigns have been emboldened by Angola’s successful reprofiling of its Chinese debt in 2020. Kenya is seeking a similar deal with its Chinese creditors and many more sovereigns may follow suit before 2024. A popular African debt myth concerns the so-called Chinese “debt trap” narrative, recently highlighted by the United States Treasury Secretary on her visit to the continent in early 2023. In fact, Chinese loan accumulation over the two decades before the pandemic amounts to USD 153 billion out of the total of over USD 700 billion, while much of these loans have been repaid, cancelled, or reprofiled. Since 2019, China has slowed lending to Africa, shown greater willingness to reprofile its loans, and offered limited debt relief.

The China Africa Research Initiative (CARI) at Johns Hopkins has contradicted the allegations of China’s “debt trap” diplomacy. A 2022 report by CARI established “that between 2000 and 2019, China … cancelled at least USD 3.4 billion of debt in Africa”. In the same period China restructured or refinanced about USD 15 billion of debt in Africa. There were no asset seizures, and China has not used legal recourses to compel repayments, unlike popularised narratives concerning Zambia’s state broadcaster, Kenya’s largest airport, or Uganda’s airport being seized as collateral by Chinese creditors – a US-driven politically-motivated narrative which has been consistently proven to be inaccurate.

Nevertheless, at least six African countries are suspected to have defaulted on Chinese loans since 2016, including Kenya, Ethiopia, Djibouti, Mozambique, Zambia, and Ghana. In comparison, only three African countries have defaulted on their Eurobond coupon payments over the same period, namely Mozambique (2017), Zambia (2020), and Ghana (2023). Mali’s payment arrears in 2022 were temporary and caused by country-specific issues. The African countries with the greatest exposure to Chinese loans on a cumulative basis have been at the forefront of bilateral debt treatments, notably including Angola and Kenya. Meanwhile, Zambia and Ethiopia are seeking relief from Chinese obligations through the more cumbersome Common Framework, which has delayed their debt treatments.

Relative to their GDP, the countries with the highest exposure to Chinese loans over the past 20 years are Angola (63 percent), Zambia (45 percent), and Republic of Congo (32 percent). But for most large African economies, Chinese debt exposure is negligible, such as Nigeria (1.6 percent), South Africa (1.3 percent), and Egypt (1.9 percent), as well as China’s fourth largest borrower Kenya (8.4 percent).

The Eurobond conundrum

Based on quantitative analysis conducted last year by Pangea-Risk and Acre Impact Capital, sub-Saharan African sovereigns are due to make USD 21.5 billion in international bond (Eurobond) repayments over the period of May 2022 and May 2027. This excludes the cost of servicing these foreign currency denominated loans. Ghana alone owes more than USD 4 billion to bondholders between now and May 2027, out of a total of USD 13 billion in dollar-denominated international bonds. Investment bank Morgan Stanley rates the average “recovery value” for Ghana’s defaulted dollar-denominated government bonds at USD 46, which is based on the country’s deal to restructure its local currency debt.

Kenya has a bond repayment bill of almost USD 3 billion for the next five years. The country may opt to issue a Eurobond with a different tenor and structured in two or three tranches to manage next year’s maturity of a USD 2 billion, 10-year bond. Such a move could give Kenya more flexibility to attract different investors and smooth out future maturities. The debt sustainability outlook of the continent’s largest economy, Nigeria, which owes almost USD 2 billion in Eurobond repayments, is also becoming more concerning.

These trends highlight the importance of proactive debt management to ensure that borrowers, which have painstakingly built their international yield curve over the past decade, continue to maintain access to deep pools of liquidity in the international debt capital markets. Issuers who are committed to building a credible investment programme that addresses environmental and social challenges will be best positioned to tap into an incremental pool of capital from sustainability and impact-focused investors.

Privacy Policy | Cookie Policy

Designed and produced by dna.studio